Writing up entries for the ‘Piston, Pen & Press’ database continually produces new findings. Even without access to our usual libraries and archives, detective work in the census records and the British Newspaper Archive regularly uncovers information that enables us to identify an unknown writer as one of ‘ours’ – that is, an industrial worker. This is a post about the first completed entry on a woman poet, Jessie Conqueror.

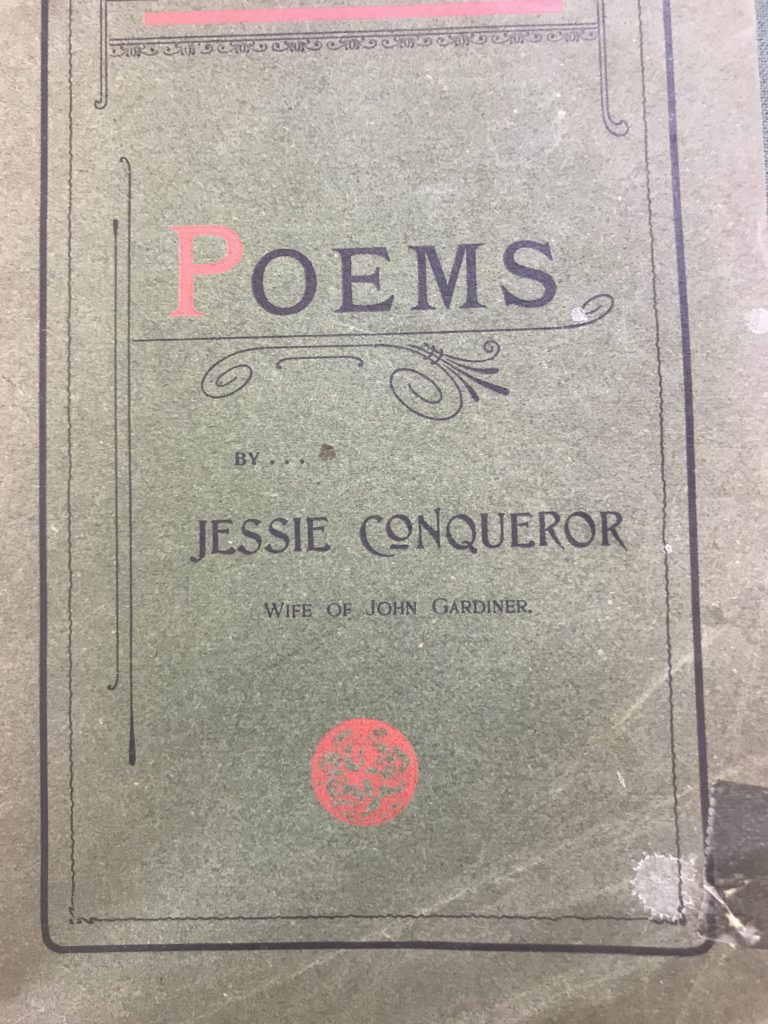

Jessie Conqueror’s posthumous Poems (1905) – which identifies her on the title page as ‘wife of John Gardiner’ – was a collection I read in Perth’s A. K. Bell Library on one of my first archival trips for this project, back in 2018. It seemed immediately clear that she could be a working-class woman poet, because of her style of writing, and because the topics of her poetry were so familiar from the newspaper poetry columns of Scotland’s mid-Victorian popular press. Pro-Gladstone poetry, for instance, is a strong signal; so are anti-Tory poems like ‘An Appeal to the Perthshire Electors’; and so are poems like ‘Lines on the Wallace Factory Excursion.’ But in this factory excursion poem, Conqueror writes from the position of an observer, not one of the workers. And though several of her poems mention the villages linked to the Perthshire bleachfields, there is no definite indication, anywhere in the collection, that she herself worked in industry.

Conqueror’s collection includes ‘Lines to Edith,’ which references factory poet Ellen Johnston, and when looking through my notes on Glasgow’s Penny Post poetry column, where both ‘Edith’ and Johnston published, I realized that Conqueror was the Penny Post poet signing herself ‘J. C., Banks of the Almond’. The Penny Post is not digitized and so cannot be easily searched, but to date I have found three poems by ‘J. C.’ within it (one is her poem on a mining explosion, ‘The Agonized Cry of the Heart’, 19 January 1867) and a mention of her in the correspondence columns. The Penny Post in these particular years in the 1860s was known to be friendly to aspiring working-class poets and had a lively poetry column featuring both male and female contributors: Conqueror must have been reading the correspondence by other women poets with interest, and perhaps was even inspired by it to try her hand at verse.

Searches in Scotland’s public records for Conquerors or Gardiners were proving frustrating, until finally the census records for 1851 produced a Janet Conqueror, aged 16, lodging with a family in Almondbank and working as a ‘linen and yarn bleachfield bleacher.’ She was born in Perth. Could this be our Jessie Conqueror? ‘Jessie’ is a Scottish nickname for ‘Janet’, and the dates fit: if Conqueror, like most of our poets, started writing in her teens and publishing newspaper verse in her twenties, she could well have been actively participating in the poetry columns in the 1860s. Conqueror’s poetry and her newspaper signature clearly suggest she lived in or near Almondbank at some point. (It is especially intriguing to wonder if she was able to make use of the nearby Banks of the Almond Subscription Library, which aimed to help local workers educate themselves.) The probability seems strong enough for us to accept that the 1851 Janet Conqueror is our poet, though she vanishes again from the records after this date.

Women industrial poets are far harder to track than male poets. For Piston, Pen & Press poets, there tends to be a direct correlation between writing poetry and being an office-bearer in other ‘improving’ groups and institutions, such as temperance organizations, church societies, and mutual improvement and ‘literary’ societies. Because the activities of all these societies are reported in the local press, male poets often come up in a name-based search in newspaper databases even when public record searches produce nothing. Male poets also frequently performed their poems on public occasions, and again, their participation was recorded in local newspapers. This is very seldom true for women poets in the mid-Victorian period, and I have not yet found any mentions of Conqueror or Janet Gardiner. Indeed, her identification as a Penny Post writer is down to chance: if she had not published a poem about a mining disaster, I would not have stopped to record the title and the author’s pseudonym.

Conqueror is an example of what we can’t find, as well as a success story. She is not only a hitherto unknown working-class woman poet, she is a working-class woman poet who wrote at least some verse about politics, industry, and the hardships suffered by the working class. Who knows what other topics her poems may have covered, as they wait to be found in the newspaper poetry columns? And, crucially, she is an example of the support networks that women poets needed. We owe a great deal to her family, and especially the elusive John Gardiner. They did not simply print Conqueror’s poems, they preserved her poems on politics and industry (which many early twentieth-century editors would have excised), and they published these under what was almost certainly her maiden name. Without this, we would have passed over this volume, setting her aside as one of the many unidentifiable and little differentiated women poets of this period. With it, she can join the canon of working-class women poets.

Jessie Conqueror, ‘Lines’

Note: This poem refers to the Huntingtower Bleachfield or Bleachworks, and in ‘structure grand’ perhaps specifically to the new main building, completed in 1866. This may be where Conqueror had previously worked, given her praise of the employer in this poem.

Extracted from J. C., ‘Lines, Composed on Revisiting a Once Familiar Spot on the Banks of the Almond’

Penny Post, 30 May 1868

When last upon this spot I stood,

It was in careless girlhood.

These changing years have left me now

A woman with a thoughtful brow;

Yet little change I here descry,

All seems familiar to mine eye:

Still from the branches high above

The cushat sends its cry of love,

The blackbird and the linnet’s note

All round in sweetest cadence float:

Still at the base of this proud height

Fair Almond glows in the sunlight

And, further on, I see her lave

Her flowery banks with pearly wave,

And fancy privilege doth claim

To think those pebbles are the same;

And still I see, beyond her bed,

Those lawns with snowy fabrics spread,

Where, proud in architectural power,

Do stand the works of Huntingtower.

And there, in many a structure grand,

Industry plys her busy hand,

And cottage homes around them spread

From that industry draw their bread,

And now around in grand array,

Those cottages I now survey,

Their owner needs no praise from me,

For sure those lovely homes must be

A monument of lasting praise

To him who did such dwellings raise;

Where beauty and convenience should

Exert an influence for good

Upon the humble sons of toil,

Too often doomed to hovels vile.

Now, as I southward turn my eye,

The same old scenes before me lie,

Where cultured lands in wide expanse,

Do meet my still enraptured glance,

And gliding still upon its way,

It o’er an upland now doth stray,

To where the hills in rugged pride

Arise, and in their grandeur hide

The scenes that do beyond them lie –

Scenes dear to nature’s loving eye.

But now I must my steps retrace,

And bid adieu to this sweet place,

This spot which memory shall revere,

This spot to love, to friendship dear.