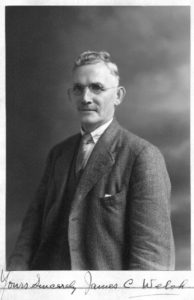

We are delighted to introduce the first of a two-part series by our guest blogger, Bill Welsh, whose great-uncle was James C. Welsh, a Lanarkshire miner who later became an MP. The second part (coming soon!) will be on James’s brother-in-law, Edward Hunter, a miner poet and trade union activist. In his first post, Bill shares his extensive family research on J.C. Welsh.

James Carmichael Welsh (1880-1954) was born in Haywood, Lanarkshire on 2 June 1880, the fourth of eleven children. His father was William Welsh (1851-1913), a coal miner, and his mother Helen Yule (1853-1932), well known locally as a singer of ‘the old Scotch songs’. The great Lanarkshire miners’ leader, Bob Smillie, wrote a newspaper article in 1917 about James Welsh’s early years. He described the period during which he was born as ‘probably one of the most miserable periods through which the miners of Lanarkshire have passed’. In his book, My Life for Labour, Smillie says that ‘Ancient Egypt never had seven leaner years than those bounded ’78 and ’85 were for the miners of Lanarkshire’.

Welsh started to work in mines in Haywood at the age of eleven and, from the humblest and most deprived of beginnings he rose to become a miners’ leader, poet, novelist and Member of Parliament. He moved to Douglas Water in 1900 and spent most of the rest of his life there.

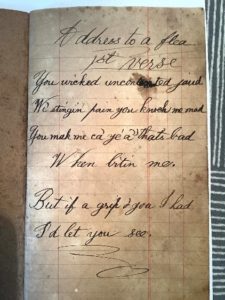

His love of poetry and literature date back to his boyhood and, amazingly, some copies of early poems survive from the early 1890s. They were written in a small notebook, which he obtained from the pit where he had started work. A label is stuck on the outside bearing the words:

James Welsh Junr.

Haywood

No. 3

These early poems reflect the origins of Welsh’s love for poetry and nature, which were to be very important throughout his life. He talked about them in interviews given after his election as an MP in 1922. He said that he began to write in secret at the age of eleven. He was out looking for birds’ nests one day and saw a skylark soaring in the air and singing its song. Although he had seen larks singing before, he seemed to see its beauty for the first time that day. ‘It was a wonderful experience’, he said. At about the same time he read a poem about the skylark by the Scottish poet James Hogg and thought that he could write one as well. He wrote the poem in his notebook and thought it was a masterpiece but, looking back, he conceded that it was far from a masterpiece. He committed several other poems to his notebook, which he kept for the rest of his life.

One of the early poems is titled ‘Address to a Flea’, which is a pastiche of the Burns poem, ‘To a Louse’, copying the format and the metre of that poem. At the age of eleven, therefore, he already had an interest in poetry and access to the poems of Robert Burns, whom he already admired, and James Hogg. Another poem is about a sleeping child at its mother’s breast, in all probability one of his younger siblings born in the early 1890s. There are also two poems about local girls he knew and one about a trip to Edinburgh.

In his later newspaper interviews Welsh said that he kept the notebook with his poems in a jacket pocket and eventually forgot about it. However, his mother was mending a tear in the jacket one day and the book fell out. She looked at the poems and asked who wrote them. When Welsh admitted that he had written them his mother said ‘Well, they’re grand’. His mother was his first critic and he still regarded her as his best critic.

Although he spent almost 25 years working underground, few of Welsh’s poems are about life in the mines. In his book of poetry, Songs of a Miner, published in 1917, he wrote more about his love of nature and he also wrote tributes to his friends and other people he admired, such as Robert Burns. He was known for much of his life as ‘the miners’ poet’, a term he disliked. He wanted to be known as a poet in his own right and not just because he was a miner.

James Welsh converted to socialism at a young age, after listening to talks given in the mines where he worked by Bob Smillie and James Keir Hardie. He was a pacifist during World War 1 and became a friend of Ramsay MacDonald, the first Labour Prime Minister. He was himself elected to Parliament in 1922 and served as Labour MP for Coatbridge and then Bothwell until 1945. He died on 4 November 1954.

Some of Welsh’s first stories were printed in serial form in the Hamilton Advertiser as early as 1905 and other poems were printed in newspapers and magazines at various points in his life. He wrote a play called Katie Kilburn, a drama set in a mining village about the seduction of a miner’s daughter by the mine manager. As far as is known it was never performed. He also wrote a novella/short story called The Black God, not dated and never published.

James C Welsh’s published works were:

Songs of a Miner (1917), a book of poems;

The Underworld (1920), a novel of life in a small mining village;

The Morlocks (1924), a novel about a miners’ strike in Lanarkshire;

Norman Dale, MP (1928), a novel about the rise of a young miner from the coal face to Parliament.

‘The Miner’ by James C Welsh (from Songs of a Miner)

Down in the deep, sunless murk, We’ve fashioned your fabric of dreams, Guiltless of laughter and mirth, Built by the gold of our blood, Playing and epic of work, Passions we spill as Life streams Here in the guts of the earth; And roars to its rim in full flood; That which was forests of trees – We laugh at the threats of your god, Flowers of the ages long gone, We’ll yet mock the things that you tell, Come we to hive – human bees – Death cannot equal Life’s load, Honey of gold for the drone. We’ll live a Utopia in Hell. You who in comfort and ease You’ve built from our lives your success, Sit by your fireside and mourn, Ye swear now ‘tis war to the knife, Torn by imagined disease, Your progress is shaped to oppress, Know ye ‘tis life that you burn, Ye spare neither children nor wife; Life in the lives of strong men The gold ye have set for your crown Crude with the task of their toil, We’ll melt in the streams of your blood, Work that’s a prayer full of pain By the god that ye worship and own Prayed to the gods of the soil. We’ll whelm all your schemes in its flood. Prayers that are curses and groans, Down in the deep, sunless murk, Agonies moulded in tears, Guiltless of laughter and mirth, Pictures in jettest of tones Playing an epic of work, Paint we to portray our years; Here in the guts of the earth; Hope of the ages we know Hell hath no terrors for men Only in times of our dreams… Born to forbear such a load, Masters, why should it be so? Scorn we its promise of pain Why should life prosper your schemes? And laugh in the face of your god.